A Tightening Grip: How Security Risks Have Shaped Strategic Risk Management in the NGO Sector (1994-2024)

Humanitarian aid organisations operate in a distinct space compared to most global businesses. Unlike for-profit ventures, their primary goal isn’t financial gain, but delivering critical assistance in crisis zones. This exposes their staff to a heightened level of security risks, often with limited resources.

While large corporations and government entities might have established security protocols and regular audits, aid organisations often lack such structures. This can be attributed to the perception of neutrality – a belief that their focus on aiding civilians shields them from harm. However, the reality is that humanitarian workers can be targeted in conflict zones due to various factors, making robust security risk management crucial for their safety.

The world of humanitarian work is one of inherent risk. Navigating conflict zones, disaster areas, and volatile environments exposes aid workers to a constant threat of violence, kidnapping, and other security breaches. This article explores the evolution of security risk management (SRM) in Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) and humanitarian organisations over the past three decades (1994-2024), highlighting key incidents that have served as stark wake-up calls and ultimately led to a more robust approach to staff safety, or duty of care.

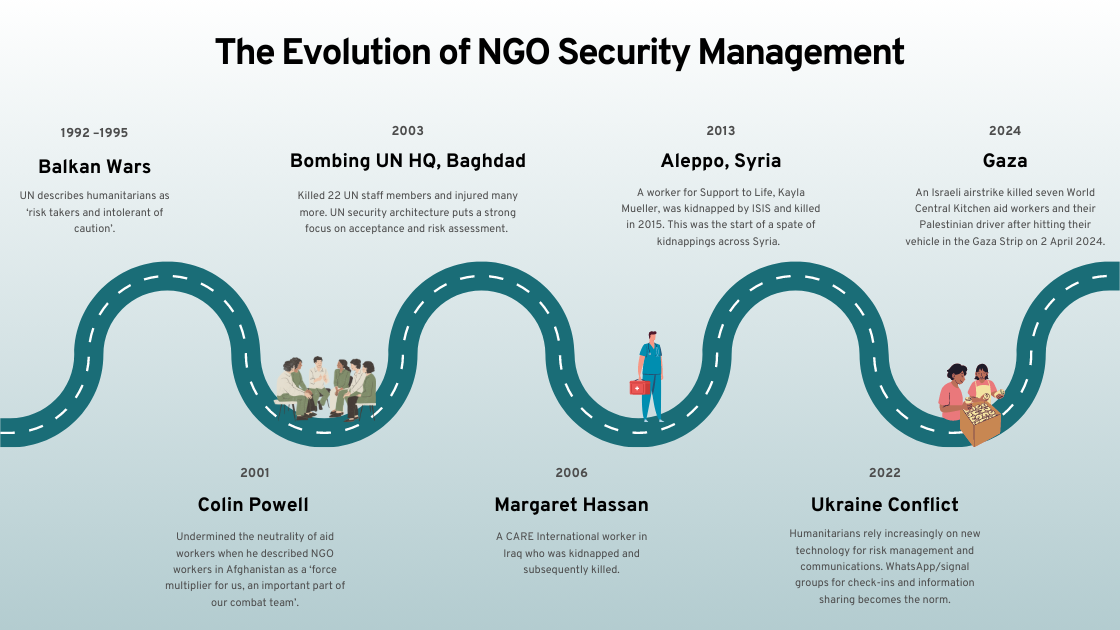

The Early Days: A Reactive Approach (1994-2003)

In the 1990’s the NGO sector was largely reactive. NGOs often lacked dedicated security protocols and relied on a sense of trust and basic precautions. A 1994 UN Agency report examining operations in the former Yugoslavia found a flawed culture and said:

“Risk-takers were viewed as courageous, while staff more concerned about security were derided for their timidity or cowardice. The sense that staff might be putting other colleagues at risk, particularly local personnel who would follow regardless of the dangers, was often not nearly as strong as the sense of setting an example of bravery.”

The 1994 Rwandan genocide, however, served as a brutal reminder of the proximity to the conflict aid workers were. The concept of neutrality also began to be questioned. Médecins Sans Frontières lost over 200 local staff in the genocide. Perhaps more shockingly, some local staff even colluded in or co-authored killings.

However, it was not until the US invasion of Iraq in 2003 that the industry began a rapid transformation. A particularly devastating event was the August 19, 2003, bombing of the UN headquarters in Baghdad, which killed 22 UN staff members and injured many more. This attack was a precursor to many more incidents of deliberate violence against aid workers.

In 2006, Margaret Hassan a CARE International worker, was kidnapped and subsequently murdered in Iraq. Her high-profile case exposed the dangers faced by female aid workers in conflict zones and the inadequacy of existing security measures.

The Rise of Professionalised Security (2003-2012)

In the aftermath of Hassan’s death, a paradigm shift began. NGOs increasingly recognised their duty of care obligations and invested in professional security expertise. Security risk assessments became commonplace, and organisations started providing staff with comprehensive security training programs. These programs covered topics like situational awareness, hostile environment training (HET), and kidnapping prevention.

This period also saw the rise of specialised security companies catering specifically to the needs of NGOs. These companies offered a range of services, including threat assessments, close protection (bodyguards), and emergency response planning. NGOs began to prioritise staff safety during mission planning, with security considerations playing a more prominent role in project design and implementation.

The Deadly Decade: Evolving Threats and the Need for Adaption (2012-2022)

The past decade has been marked by a surge in violence against aid workers. The Syrian Civil War, the rise of extremist groups like ISIS, and the increasing complexity of conflict zones have all contributed to this dangerous environment.

The pressing need for this was highlighted by the case of Steve Dennis, a Canadian humanitarian who was abducted in Dadaab, Somalia while working for the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) in 2012. Following his release, Steve began questioning the NRC risk management procedures and in 2015, In 2015, won a precedent-setting legal victory in the Norwegian courts. Authorities determined that the risks were foreseeable, and the NRC was found to be grossly negligent in terms of understanding and managing these risks by key decision-makers.

The humanitarian sector paid attention and the major aid agencies began further professionalizing their approach to duty of care.

At the same time a steady mounting of casualties from around the world spurred further advancements in security protocols. In 2011, The United Nations publishes a study outlining ways organisations can maintain operations in high-risk places, emphasising the need to focus on risk acceptance and realization that risk aversion was a nonstarter.

NGOs began to prioritise localised security expertise, recognising the value of understanding the specific threats and cultural nuances of each operating environment. This has however led to many challenges regarding remote management.

During this period, technology also played an increasingly important role, with communication tools and tracking devices becoming essential for staff safety.

The Future of Duty of Care: A Multi-Faceted Approach (2023-2024 and Beyond)

Looking ahead, the concept of duty of care is expanding to encompass not just physical safety but also psychological wellbeing, sexual harassment prevention, and ensuring a safe and secure working environment for all staff members.

The landscape of security risk management in the NGO sector is likely to be shaped by several key trends and areas that need particular attention are:

Mental Health and Wellbeing

The psychological impact of working in high-stress environments is gaining more recognition. NGOs are placing greater emphasis on staff mental health and wellbeing programs, including access to counselling and psychological support.

Technological Advancements

Advancements in technology; risk assessment software, real-time threat monitoring and artificial intelligence are likely to play a bigger role in security risk management. These tools can provide NGOs with a more comprehensive understanding of potential threats and allow for more targeted mitigation strategies. Better working practices and processes can also be streamlined to help over stretched humanitarians.

Cybersecurity

As NGOs become increasingly reliant on technology, cybersecurity threats are becoming a growing concern. Organisations are investing in robust cybersecurity measures to protect sensitive data and staff communications.

Conclusion: A Never-ending Journey

The journey towards ensuring the safety of aid workers is a continuous one. Currently with conflicts in the Middle East and Africa raging, the casualty count is frighteningly high. As of April 30, the UN reported that 254 aid workers had been killed in Gaza since October 7, 2023, with UNRWA personnel accounting for 188 of these fatalities.

NGOs and humanitarian organisations must remain vigilant, constantly adapting their security protocols to the ever-evolving threat landscape. By learning from past tragedies and embracing new technologies and approaches, these organisations can better fulfil their duty of care and ensure that their staff can continue their vital work in a safe and secure environment.

Protect your NGO with RiskPal’s comprehensive risk management services. As security threats evolve, our risk assessment software helps you adapt, ensuring the highest duty of care for your personnel. Learn more about how RiskPal can support your organisation’s risk management efforts at RiskPal or contact us for more information.